Web accessibility becomes easier and cheaper, when you address it earlier. In this post, we’ll look at various ways to do that, like picking the right CMS and making accessibility part of the agile process. Combine them for maximum effect.

A quick disclaimer before we start: while this post is about web accessibility, the same probably goes for web security, web privacy and other important aspects of a healthy web.

To make websites accessible, most organisations choose to follow the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). It’s also the standard most governments embed in their rules. Meeting WCAG does not guarantee accessibility, but the standard is a good baseline. It is our best bet as a shared understanding of what ‘this is accessible’ means.

Choose a CMS that helps with accessibility

WCAG is about the accessibility of content, so it makes sense to optimise what we do when we create content. We could pick CMSes that help editors create accessible content. In my talk “Your CMS is an accessibility assistant”, that I did last year, I discuss just that.

What if a CMS, when you add a video, prompts for subtitles? What if it, when you place text on a hero image, it helps you pick a color that has sufficient contrast, or suggests to add a background color? Some CMSes already ship with features like this.

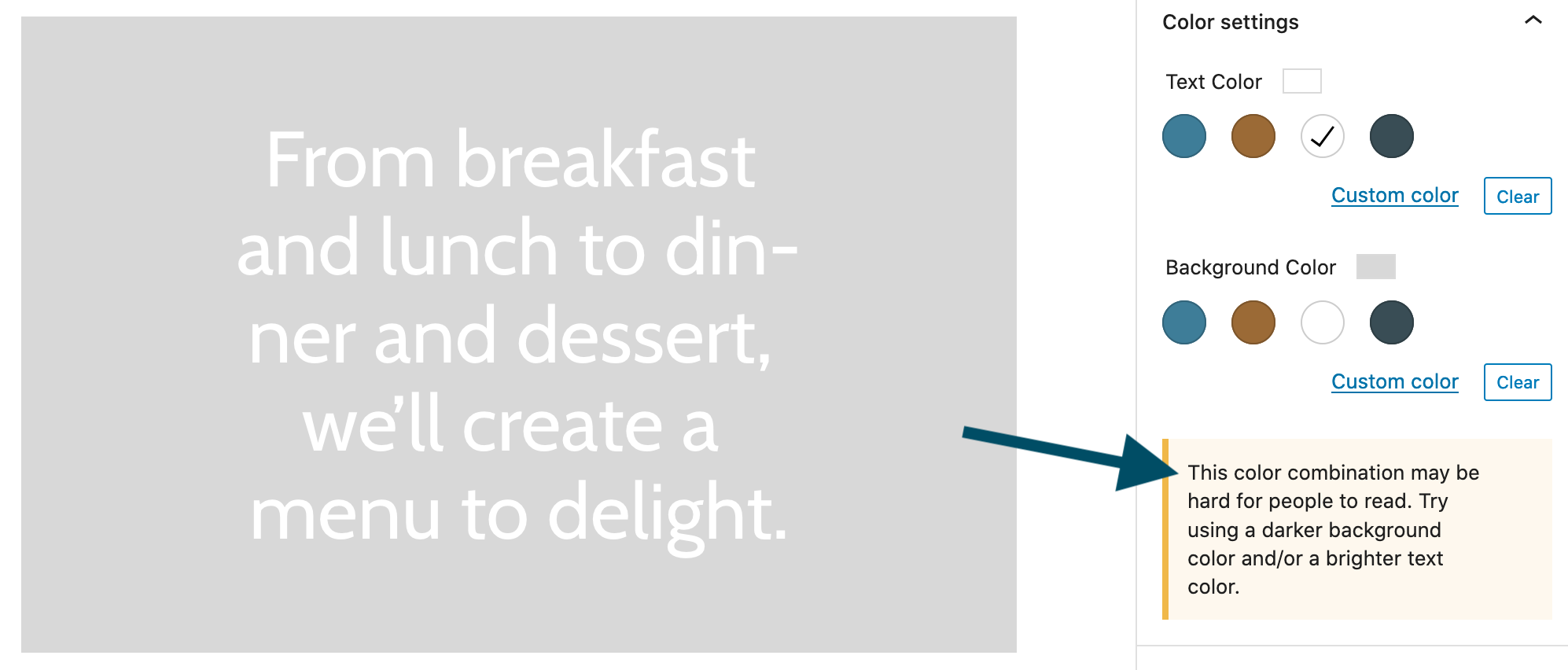

WordPress’s Gutenberg editor, for instance, will tell you when you’re starting to use colours with insufficient contrast:

Features like this are super helpful, because they let us spot accessibility issues early in the process. Without them, we may have only found out about problems once the functionality went live and got audited. With good early warning systems, WCAG audits can focus on the more complex issues.

Check accessibility with every user story

A lot of web projects rely on some form of agile project management, many move new functionality through a set of stages. If you can build accessibility steps into the process, somewhere before the last stage, you can find and fix accessibility problems before they go live.

There are many ways to do this. You may not want to do a full WCAG audit on each piece of functionality, but I’ve seen teams leverage checklists that address low hanging fruit. When you combine a bunch of fairly easy to execute manual checks with some automated accessibility checker, you will likely be able to address problems while they emerge. For instance, add that keyboard handler while you’re building the widget, rather than following a formal accessibility audit months after the feature initially launched.

Some checks you could include are:

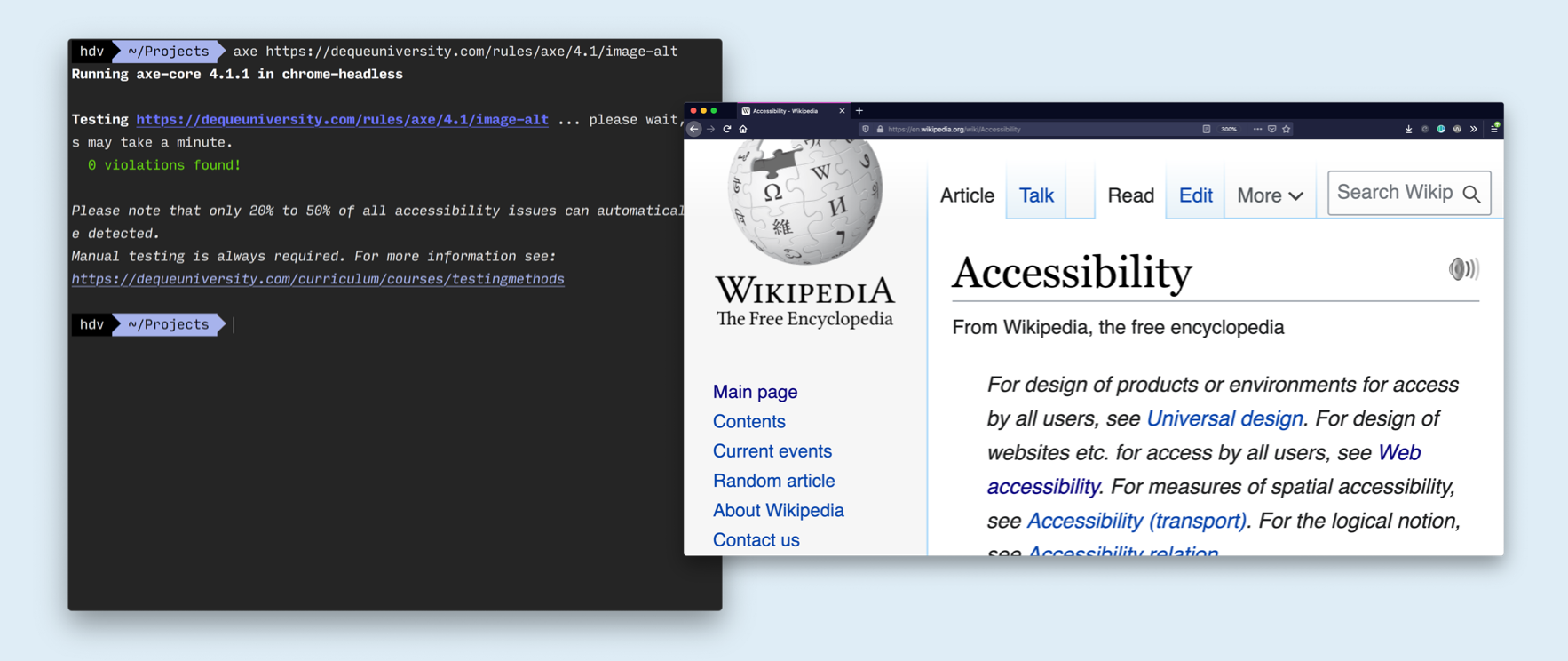

- do the automated checks (for instance from axe-core, Tenon, Polypane or Siteimprove) return zero issues? Note, automated checks can only check 10-30% of WCAG issues, don’t rely on just automated checks

- can all controls in the feature be used with only a keyboard?

- can you still use everything if the browser is set to 400% zoom?

- for all form inputs, does the input activate when you click on the label?

Checklists have caveats though… the most important is to realise that “what’s most easy to check” is not necessarily the same as “what’s the most important to check”. It would be quite the coincidence if it was. But having said that, easy checks are probably the checks that are most feasible to include with each piece of functionality.

Level up on HTML proficiency

A large portion of issues I find in my WCAG audits relates to HTML and how to use it. Developers who know the HTML spec inside out are at a massive advantage when it comes to the WCAG compliance of the product they work on. Which elements to use when, how to build forms, what attributes exist for tables… it will all help write more accessible code.

For instance, developers who are aware that input-elements have an autocomplete attribute, will have no trouble meeting Identify input purpose (Success Criterion 1.3.5, which requires that attribute for form fields that collect personal information).

Ensuring new developers can bubble sort may be important to your business goals, but so is testing for HTML proficiency. Even, maybe especially, when you interview a full stack developer for your team, make sure you also interview for the HTML bit of the stack. It will help the team create accessible code from the start.

Wrapping up

In conclusion, with the right CMSes, checklists for every user story and high levels of HTML proficiency, teams can get a lot of their accessibility right early in the process. These all may all seem like no-brainers, but I’ve only seen very few organisations adopt them. I’m curious if others have more strategies for putting accessibility earlier in the process, please do reply via email or socials, or in the comments below.

Comments, likes & shares (2)

and Zach Leatherman liked this

ATAG is a set of guidelines for the accessibility of authoring tools. In this post I'll talk about what it is and why it matters.

Most people working on websites will be familiar with WCAG, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. There are two more related standards, one for user agents (like browsers) and one for authoring tools (like CMSes, WYSIWYG or Markdown editors, e-learning platforms and website creators). They work together: if we care about the accessibility of web content, we should also care about how it is created (in authoring tools) and displayed (in user agents).

“Web content” in accessibility standards refers to websites, apps and other content on the web. I like to think of it as the HTML that browsers serve to the user when they access your website or app. There isn't a definition for “web content” in WCAG, but there is one for “web content technologies”. From that definition we can draw that web content includes anything that is rendered by user agents, like HTML and SVGs.

Why ATAG matters

Better accessibility of content tools is critical for three reasons:

Let's look at these reasons in a little more detail.

Content creation is for everyone

‘The web is for everyone’, as web inventor Tim Berners-Lee likes to say, applies as much to accessing websites as it does to creating them. His first browser had both viewing and editing capabilities, so clearly the web was always meant to be about both consumption and creation. Many of us love to create vlogs, set up online classes, publish recipes, tweet, make TikToks, create art… this should just work for people with or without disabilities. If content creation tools have barriers, that's everyone's loss.

In business, it would be illogical (and illegal) if you couldn't hire content professionals with disabilities, just because they can't use your content tools. In your company today, Harry from marketing might be able to use a mouse, but when he leaves his successor might only use keyboards.

Support for all of HTML

The second part to authoring tool accessibility is their ability to output accessible content. Imagine two tools to create bulleted lists. One does this with

divs and images of bullets, the other uses the standardulandlielements. The latter is what we need, and not just when dealing with lists, but for all kinds of markup:tableswithcaptionsvideoswithtrackelements andmutedandautoplayattributesfieldsets withlegendsaltattributeslangattributesNot all tools let you create all or these structures, at which point they basically become the accessibility issue.

Authoring tools as accessibility assistants

Even cooler than outputting sensible and appropriate markup, authoring tools could provide hints. They could try to be a helpful “accessibility assistant”, by point our potential barriers when they notice you're creating them. For instance, if an authoring tool lets you pick a foreground and background colour, it could warn you when you pick two colours that have insufficient contrast.

ATAG recommends various ways of assisting with making content more accessible: accessible default components and templates, solid documentation and, as described above, suggestions and hints.

Who meets ATAG

At the time I am writing this, I am not aware of any authoring tools that meet 100% of ATAG, as in, all criteria at level A or AA. That doesn't mean all is lost, every bit helps and there are a lot of authoring tools that meet many bits of the standard.

With the ATAG Report Tool, people can create a report with specific details about which parts of ATAG they do or do not meet.

As described above, there are lots of good reasons to try and meet ATAG. It is a worthwhile pursuit for authoring tool makers and a worthwhile request for procuring departments to put in tenders.

What's in ATAG

There are two parts to the ATAG standard:

If you're still with me, I'd like to describe ATAG in a bit more detail. Like WCAG, ATAG has Principles, Guidelines and Success Criteria. In the following sections, I will discuss the Principles and Guidelines in my own words. Full and official wording is in the ATAG 2.0, published by the W3C. This is not legal advice.

Authoring tool UI meets accessibility guidelines

The full editing experience conforms to WCAG 2.0 or other accessibility guidelines. (A.1.1)

The interface conforms to platform-specific accessibility guidelines. (This one specifically applies to authoring tools that are not web-based, which was more common when ATAG came out) (A.1.2)

Editing UI is perceivable

If there is anything visible that is not text, like icons, images or video, there is alternative text available. (A.2.1)

Status indicators (like changes or spelling errors) and text properties (like italics or bold) are conveyed to users of assistive technologies. (A.2.2)

Editing UI operable

Everything that can be done with a mouse, can just as easily be done with a keyboard, including drag and drop and drawing capabilities. There should be no keyboard traps. Keyboard usage should be efficient and easier to use than just with sequential access (for example: use WAI-ARIA landmarks or offer keyboard shortcuts). (A.3.1)

Time limits in the editor, like for auto-save, can be turned off or extended (some exceptions apply). (A.3.2)

Flashing content, like videos, including previews of that kind of content, can be paused or turned off. (A.3.3)

Users can navigate quicker by structure, for example headings, lists or HTML elements. (A.3.4)

Users can search in text content, results are focused when shown. If there are no matches, this is indicated. User can search in two directions (backwards and forwards). (A.3.5)

If there are user settings for display, this only affects the editing view, not the output. If a content editor uses OS settings like high contrast mode or their own stylesheet, this does not break the editing experience. (A.3.6)

When the tool shows a preview of the content, that preview is at least as accessible as in current browsers and other user agents. (A.3.7)

Editing UI is understandable

The tool lets users undo changes and settings. (A.4.1)

The tool has documentation for all features, including accessibility features. (A.4.2)

Fully automatic processes produce accessible content

When the tool generates markup, that markup is accessible. If accesssibility information is required, like alternative texts, the content editor is prompted to provide that information. (B.1.1)

If content is pasted from a word processor or converted from one format into another, any accessibility information is preserved. (B.1.2)

Supports producing accessible content

If some options produce more accessible content than others, they are displayed more prominently. If properties and attributes can be set, those relevant for accessibility can also be set. (B.2.1)

Editors are guided to produce accessible content. (B.2.2)

There is a tool for providing text alternatives to “non-text content”, like images, videos and data visualisation. (B.2.3)

There are accessible templates available. If there is a repository of templates, it is easy to find the ones that prioritise accessibility. (B.2.4)

If any components or plugins are built-in to the tool, they are accessible. If there is a gallery of components or plug-ins, it indicates accessible options. (B.2.5)

Helps with improving the accessibility of existing content

Has built-in checks for common accessibility problems, for example a check to identify missing alternative text. (B.3.1)

Provides suggestions to content editor about accessibility problems. (B.3.2)

Promotes and integrates accessibility features

Accessibility features are on by default and a prominent part of the editing workflow. Documentation shows examples of how to create accessible content, for instance with example markup or screenshots. (B.4.1)

The tool provides suggestions to content editors about accessibility problems. (B.4.2)

Wrapping up

In summary, ATAG recommends two things:

The instructions are more detailed in the standard, but that's what it comes down to in most cases.

Though the standard is only met at most partially by most tools today, a wider landscape of ATAG-supporting tools would be fantastic for web accessibility (because it's easier when you do it earlier). Increasingly, authoring tool makers start to realise this and that is wonderful.