The first hour of CSS Day 2017 was truly memorable, as the very inventors of the language took the stage. They brought back memories of the early days of CSS. It was the year 1994. There were lots of documents and they needed styling.

One of the things that stood out for me was their discussion of what they wanted CSS to be: as simple as possible. This is a thing today’s CSS language still resembles. Want something to have a red color? something { color: red; } is all you need. But while the language itself is simple, the structures we build with it today are often not.

Really, ‘simple’ is not a qualification suitable for the CSS codebases I have worked on in the recent past. The same might go for you. Near the end of the session, someone mentioned Internet Explorer has a maximum of 6000 or so CSS rules allowed (4095, actually). Bos and Lie wondered whether anyone would need that many rules. With some embarrassment, I’ll admit that I once worked for a large Dutch consumer brand where we encountered this maximum, and ended up splitting our stylesheet into two separate stylesheets.

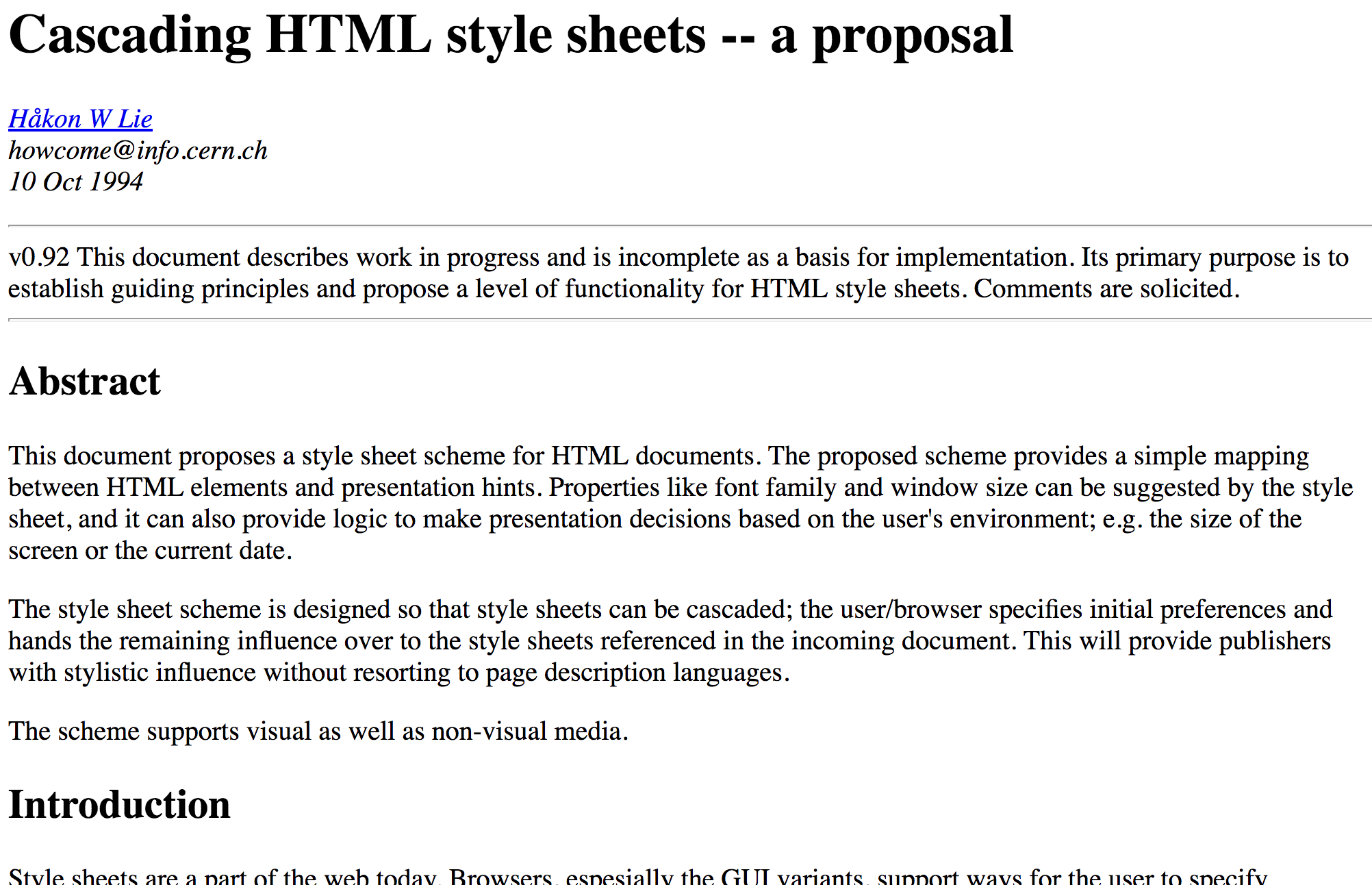

Screenshot of the proposal for Cascading HTML Style Sheets

Screenshot of the proposal for Cascading HTML Style Sheets

Simplicity was a core design principle

From the early mailing lists and the proposal of Cascading HTML Style Sheets to Håkon Wium Lie’s PhD thesis about stylesheets, which reads as a detailed account of CSS’s genesis: there is quite a bit of information on the web about how CSS was designed. Keeping it simple was a core principle. It continued to be — from the early days and the first implementations in the late nineties until current developments now.

Authors can specify as much or little as they want

CSS authors can use the language to just set a font and line height for a document and leave it at that, or they can completely change the appearance of it. The cascade ensures this: even if no rules are applied by the CSS author, there is still the browser stylesheet or even user stylesheet to provide hints as to what the page should look like. Yes, the cascade is a principle that provides simplicity, not complexity.

It is not a programming language by design

CSS is a declarative language on purpose. It could have been a Turing-complete programming language, which would have been more powerful, but bad for simplicity: difficult to read and expensive to maintain. As Bert Bos mentioned in the session: ‘we wanted it to be so simple that everyone would be able to use it’.

They are agnostic as to which medium they are used for

From the early days, CSS has had @media constraints, so that authors could write different CSS rules for media like print and screen. All optional; if not specified, the rules would apply to all. They came up with ways to specify which medium some style rules are for, but most importantly, they thought about the applicability of the language outside the medium they were looking at then.

It is stream-based

Browsers can do progressive rendering, which means they show the document incrementally, while it is still downloading. It was important for CSS not to break that principle, which is the reason CSS is “stream-based” (as opposed to being a transformation language, which would allow more features, but also increase complexity).

To summarise: CSS itself was kept simple, and it was designed to support unknown as well as existing stuff (and to not break that). It is non-intrusive, which I think is a characteristic that is hard to find in complex systems.

What has changed since?

So, let’s look at what makes modern CSS complicated. With modern, I mean after the late nineties. I think there are a couple of things.

Websites have become more than documents

CSS was made to style documents. At the time, they were things like a long Word document — think academic papers, reports and the like. Early CSS features aided those kind of documents: there was generated chapter and section numbering, ability to style the first line and page margins.

Although we still call web pages documents, (I mean, who doesn’t document.querySelectorAll ?), they are often more than that. We now have loads more websites where you do stuff, rather than just read things: from transferring money to booking travel.

Tooling

I think hardly anyone still writes CSS by hand, I mean, in a .css file. I do it on some sites that I run myself, but it’s been a long time since I’ve seen it in my client’s codebases.

Often, the reason is that CSS is written per component, with different files, and tooling is used to combine them into one file (@import would be too many HTTP requests). Other reasons are variables and mixins that are used with the goal of DRYer code (the latter, I think, can be quite problematic).

Graphic design for the web professionalised

Early web pages often hadn’t a dedicated or professional designer. Most modern websites do. There are specialised teams caring in detail for branding and user experience, and this demands a careful approach to writing CSS. Front-end development teams adjusted their practice, they sometimes agree upon a systematic approach to classnames. They often prefix classnames with the project name (for this site, I could start all classnames with hv-). Some companies distinguish between objects and utilities and prefix those (hv-o-thing, hv-u-thing). Also, they have agreed on mostly using classnames as selectors, not IDs or tags. Attribute selectors are controversial in some companies (I personally love them).

Control over content and markup

CSS has always been able to work on unknown markup, but things have gotten more complicated in the sense that more content is now user generated, content changes faster (i.e. on news websites) and more markup has been abstracted by powerful and complex CMSes.

Component based architecture

Lots of companies have switched to a component-based approach, where they design and build components that can then be put together in whichever way they see fit. For CSS, this means that elements can be inside different parts of the DOM tree. This is why many CSS authors that work on component libraries choose to create different ‘scopes’ (in classnames, with something like BEM).

Although things have changed, the basic idea is still that values/properties apply to things, and as an author, that’s the only thing you need to worry about. You don’t have to have build steps and you still don’t have to specify how styling, including complex grids, should be computed. You don’t even have to specify what everything looks like, as there are defaults and your own settings cascade. However, if you want to have build steps or have more fine-grained control, you can! Houdini will provide the latter, while keeping the basic ideas of CSS, like the cascade and media constraints, for you to use.

I think lots has changed since the early nineties, but not really things that touch on how we apply CSS to structured markup.

Today

Most of the early-day thinking about CSS still applies today (and is still very much there in more recent additions to CSS specs). That is kind of amazing to me, because it is over 20 years old. In the world history, that does not seem like much. But looking at what kind of devices and browsers existed then, it is quite astonishing.

I like to believe that the simplicity of CSS as a language is one of the reasons that it still works so well. Efforts to componentise CSS (to get programmatic scope) and bring CSS into JS can bring huge benefits and make things more manageable. But they definitely also increase complexity. Increasing complexity is a choice, and in the early days, the web community chose simplicity over complexity. They had good reasons for that choice, and it is a choice that has served many for over 20 years.

Modern websites are different and so are our coding practices, but in the grand scheme of things, not a lot has changed. If we are to willingly increase complexity of our CSS code with shiny new tools, that’s fine, and CSS is quite suitable to build tooling on top of. But, we should have good reasons for introducing complexity (and definitely read more about CSS’s making of).

Comments, likes & shares

No webmentions about this post yet! (Or I've broken my implementation)