Last week I joined over 400 web nerds at CSS Day 2019, which took place once again in the lovely Compagnietheater in Amsterdam. These are some of the things I learned.

The badges were beautiful and there were smoothies (

The badges were beautiful and there were smoothies (scroll-behavior: smoothie)! Speakers from left to right: Natalya Shelburne, Rachel Andrew, Tab Atkins, Heydon Pickering. Photos on the right by Joyce Goverde, the event’s awesome photographer

When I attended the first installment of the conference, I had not expected that there would be more. I mean, there’s only so much you can say about CSS. Of course I was wrong and more happened… every year. Last week was the 7th (!). The 2019 edition was not, as tweets may have suggested, a day for bashing JavaScript or the people who write it. Apart from the occasional tongue in cheek comment on people’s motivations to pick React (React?), this conference was full of interesting tidbits on what CSS can do now, how it is being developed (in specs and in browsers) and how we can, as CSS developers, be effective team members, able to sell CSS as the serious language that it is. With all due respect for our colleagues who write JavaScript (I and many others do both, too).

Note, I missed the first talk (the good thing about a conference nearby is: can do some daughter time in the morning). Luckily Rachel Andrew’s video and Rachel’s slides are already online, I just watched the video and it is very, very good. One great point she makes in it is that we should stop talking about CSS as if it is a hack, because if we do we reinforce the idea that CSS is weird, quirky and a series of hacks. She said this in the context of using auto margins for alignment, which she said is simply using CSS as it is specced, not a hack.

What CSS can do now#heading-1

Something you might not think about daily: when should lines break? Florian Rivoal showed how whitespace between words works on the web, and what some of the challenges are in deciding when to break a line to the next (Florian’s slides, Florian’s video). This is specifically interesting within tables, as a cell that contains a long line of content increases the whole table’s size, unless the line breaks. The same happens in Grid Layout cells, by the way. Breaking is defined in Unicode, annex 14, you can automate with auto hyphens (always set a lang and star the Chromium bug to express interest in support) or manually influence with <wbr> or a soft hyphen character.

Steve Schoger showed tips and tricks to make websites look better (Steve’s video). No actual CSS was shown, but it was interesting to see how small visual changes can make a big difference. Think about how to choose the right colors, create visual hierarchy and design good tables. A great tip regarding tables was: they don’t have to represent your database structure: often you can show less columns by combining or omitting some information, and make the core information easier to find. It was good to see that in many of his tips, Steve also took accessibility into account.

Heydon Pickering introduced how smart CSS can let flexbox layouts resize between linear one column things and multiple columns, without that weird in between state where the last item takes double space and therefore looks more important, and, importantly, with no media queries (Heydon’s video). They depend on window width, which is not helpful in a world where components can exist in all sorts of containers. His solution is aptly (?) named the holy albatross, and in his talk he revealed a project called Every Layout where that technique and others will be made available as custom elements, built together with Andy Bell.

How it is being developed#heading-2

Line boxes have existed for ages in CSS, Elika J. Etemad a.k.a. fantasai explained, they ensure content does not overlap (fantasai’s video). But, non-overlapping content could mean a less ideal vertical rhythm, and this annoys typographers working with CSS. The definition of ‘fits within linebox’ may need to be redefined, Elika explained, there may be a switch between this old and new model for how lines are sized. What if you have a graphic or heading on a page that is not as tall as exactly X amount of lines? That would interrupt the vertical rhythm. To deal with that, CSS might get a block-step-size property that could insert extra space above and/or below that graphic, to fill the gap between the space the graphic needs and the space the vertical rhythm offers. You would even be able to choose whether to add it as margin or padding (with block-step-insert), and where to align it (block-step-align: auto | center | start | end). This is all defined in CSS Rhythmic Sizing, currently open for feedback. Elika also went into linebox trimming with leading-trim-over/leading-trim-under, which gives better control over leading in the top and bottom of a text, to allow for alignment without magic numbers (see #3240). Interestingly, for this to work, it’s not just CSS, but also font foundries, who need to add the required metrics. Font metrics are also important for baselines (in future CSS you can set a dominant baseline with dominant-baseline (TIL there are multiple baselines)) and drop caps. For all of these things, languages beyond English (including CJK: Chinese-Japanese-Korean), are very much taken into account by spec writers, because the web is for everyone.

Manuel Rego Casasnovas showed how CSS is developed as features inside browsers: what the steps are to follow, what kind of actual C++ code goes where in the code base and how features go from existing behind flags to stable browser features that will forever exist because backwards compatibility (Manuel’s video). One of the many interesting things I learned in this talk is that it takes hours to compile a browser.

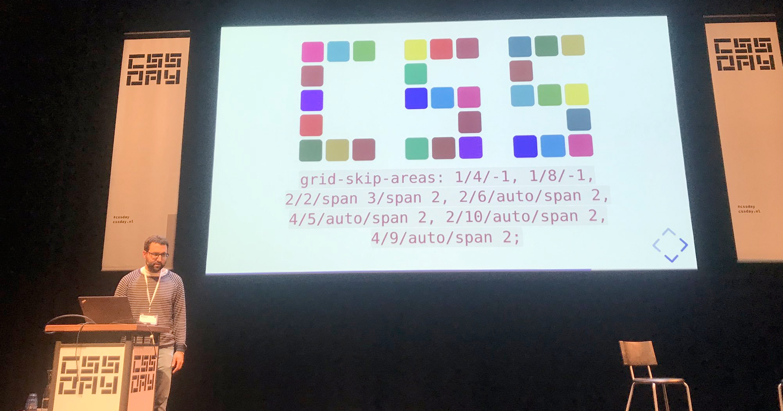

If we had

If we had grid-skip-areas, we could choose to autoplace grid items in all areas, except some. Then we could create the word CSS out of a grid.

Being a CSS developer#heading-3

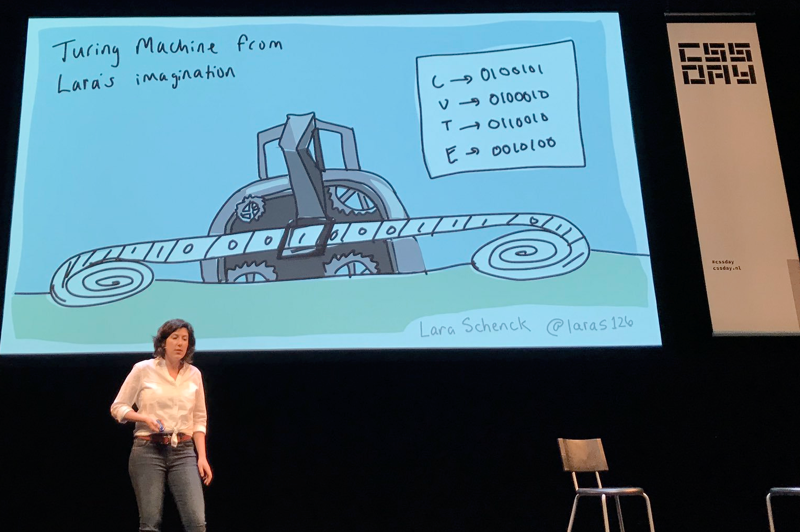

It is unlikely for a question to attract as many trolls online as: ‘is CSS a programming language?’ Lara Schenck decided to do the research and shared her results with us in a talk that was excellent in so many ways (Lara’s slides, Lara’s video). CSS fits right into one of the programming paradigms, domain-specific declarative programming languages, Lara explained. There are lots of criteria sceptics could come up with, like that programming languages should be Turing complete, suitable to write algorithms in and ‘have consequences’. She addressed these brilliantly in a sort of Socratic dialogue. Yes, you can replicate rule 110 in CSS with :checked and :not(), ok and a user and HTML, you can (and probably should) write CSS algorithms that are groups of declarations to produce a specific output, and yes, CSS has consequences, that can be addressed with programming methodologies. A great serious note she ended with is that a consequence of labeling CSS as “not programming” is that it renders companies unable to hire people who are good at CSS. People see it as not a skill worthy, and this is a problem, because without good CSS developers, companies lose out on well-built front-ends. To add a data point: I see this phenomenon almost everywhere I work (sadly).

Lara’s Turing machine

Lara’s Turing machine

Natalya Shelburne talked about the mindset of people who write CSS and how it combines different mental models (Natalya’s talk). She talked how CSS developers can bridge the gap between designers and the actual application’s you’re working on. One tool that helps is design systems: it can bridge domains, enforce shared vocabularies. Another cool thing she showed was a special ribbon like menu that she deploys just on staging. It has tools to help designers understand grids and, amazingly, the boxes that exist in the CSS reality, as compared to the boxes that are in the designer’s software. What an awesome way to collaborate! Natalya also discussed technological barriers: by moving a lot of our code into React components that are written in a way that’s mostly optimised for reading the JavaScript that exists around it, highers the bar for pure CSS people to contribute. She suggested having a pure HTML/CSS version to allow designers to contribute. Rather than thinking about or sticking to certain technologies, we should think about how to enable people, Natalya said. She celebrated that there are lots of people in the web community doing great work in this space.

Wrapping up#heading-4

It was really good to see some new CSS that is coming up (seriously. watch fantasai’s video) and learn about how to use existing CSS. Another recurring theme throughout the day was: as a community of CSS people, we should demand this language we love to be taken much more seriously. If not for our own sanity and valuation, then for the companies we are writing CSS code for. I urge you to watch Lara’s video and Natalya’s talk.

One call to action that a couple of speakers mentioned in talks and in the hallways: please have a say in how CSS develops, all discussions happen on GitHub, everyone should feel free to comment. Blogging about things you’d like to see or use is also encouraged.

The CSS Day organisers have once again set the bar very high for the next edition, let’s hope there will be another one in 2020!

Comments, likes & shares

No webmentions about this post yet! (Or I've broken my implementation)