Pretty much all of my projects in recent years have involved pattern libraries: setting them up, promoting their usage and coding actual patterns. So when Jeremy Keith of Clearleft announced he would host a Patterns Day, I bought a ticket instantly. A full day of design system nerdery sounded like a great thing to travel to Brighton for. And it was definitely worthwile…

Pattern libraries can be hard to get right: not only do you need to gather patterns and put them in a library, you’ll likely also want to avoid code repetition, make sure they integrate with your application code, get others in your organisation to care for and use the library and find a way to make the distinct modules you’ve created form one sensible whole. Patterns Day conference covered all of these subjects and more.

Audio of the day is available as podcast on Huffduffer, videos have also been recorded and will probably follow soon.

The talks

The conference had a fantastic start with Laura Elizabeth, who talked about selling design systems. She said they are great as they ensure consistency, shared vocabulary and understanding of the medium for less technical people. They also have problems: keeping them maintained is hard, they are a lot of work (often underestimated), and there is a chance they won’t be worth the investment. Laura explained that making the case for design systems can be a two step process: first, find a common pain, then gather data. According to her, a pattern library works when the need for it is equal to or larger than the effort require to build it (and that effort is usually huge). My main takeaway from this talk was: if you want to do well at selling your pattern library, be aware of potential shortcomings and gather data to support your claims.

The second talk of the day was by Ellen de Vries (we’re not related, not as far as I know anyway). Her talk was lots more theoretical and went into what it means for a system to be coherent. One way to improve coherence, and this is something we can learn from architecture, is to look at more than just the parts and consider the usage of our designs by people and the larger world around the design (when a performance area is designed for a park, the designer could consider what the charge for attending concerts should be). A story in books or films can be defined as personal experience in space over time. A story in books is a more fragmented experience: content guidelines can help users make more sense.

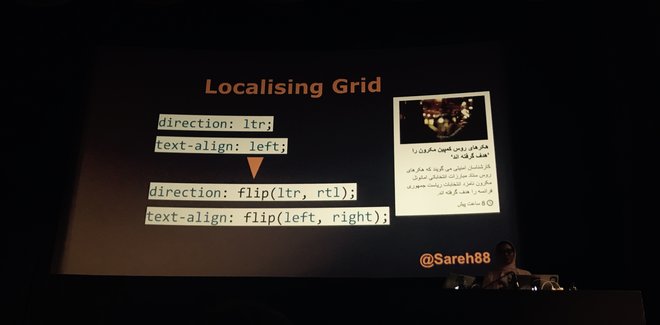

After the break, Sareh Heidari took the stage. She works at BBC News and told us about both their design language (GEL) and their approach to CSS architecture (Grandstand). Turning things into a pattern helps avoiding the repetition of CSS. Grandstand has namespaced objects and utilities, but also mixins to aid localising typography and grids. These mixins effectively turn direction-dependent properties into direction-agnostic ones, so that one rule can be used in generation of stylesheets for both left-to-right and right-to-left languages. Sarah also emphasised how important communication is, if you want to keep your codebase lightweight (challenge those who want to add new variations, they might not be absolutely necessary).

Sareh Heidari explaining mixins for localisation

Sareh Heidari explaining mixins for localisation

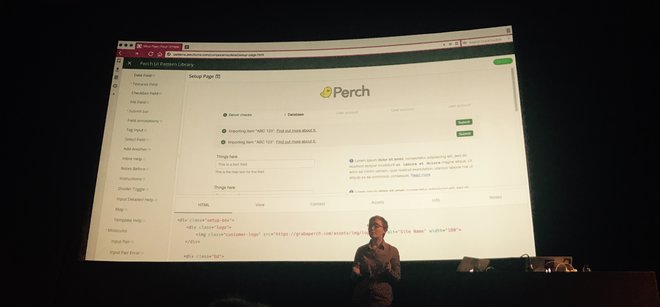

In the next talk, Rachel Andrew discussed two bits of software I use almost daily: Fractal (a component library tool) and Perch (the CMS this website runs on). She recommended making your pattern library the single source of truth for UI styles (as the Perch one is for Perch’s UI), and choosing a pattern library approach that makes renaming trivial (as Fractal does) so that you don’t need to worry too much about naming. A pattern page is like a reduced test case, Rachel said, and they’re great for experimenting in isolation. I had never thought of it like that, but realised that is certainly something I use pattern pages as.

Rachel Andrew showing Perch’s Fractal instance

Rachel Andrew showing Perch’s Fractal instance

After the lunch break, Alice Bartlett talked about the Financial Times’ Origami pattern library, specificly about what’s next when you’ve built your actual library. She explained templating is ok for a specific stack, but hard (impossible?) to do right if your organisation has multiple stacks. No templating at all is likely a bad idea that causes duplication and makes simple changes like classnames hard. Serving CSS/JS is easy if you serve everything always (can work if your site is not too complex), but separation can be done. Origami has a repo for each individual pattern so that projects that use it can use just what they need (or include just that from the Origami CDN if they don’t want to bother with asset management). Rule for all of this: choose the simplest for the job (the best tooling is no tooling!). Alice also went into non-technical aspects of pattern library success in big organisations: have fantastic documentation, put effort in making sure people in your organisation are aware the pattern library exists (so: do marketing, basically) and have a support channel and incident reports.

Jina Anne did something completely different and read a story to us, which was beautifully illustrated on the slides that complemented it. I’l have to refer you to the videos for this.

Paul Robert Lloyd let us look at the bigger picture, with some interesting examples from architecture. He asked a number of thought-provoking questions about how our choices are informed: is there room for irrationality when our design systems embrace mathematical precision, do the tools we use dictate our approach to design systems (like Photoshop’s ’New File‘ screen asking for dimensions), does culture affect our decisions and do we serve the interests of the organisation we work for or those of the people affected by our work?

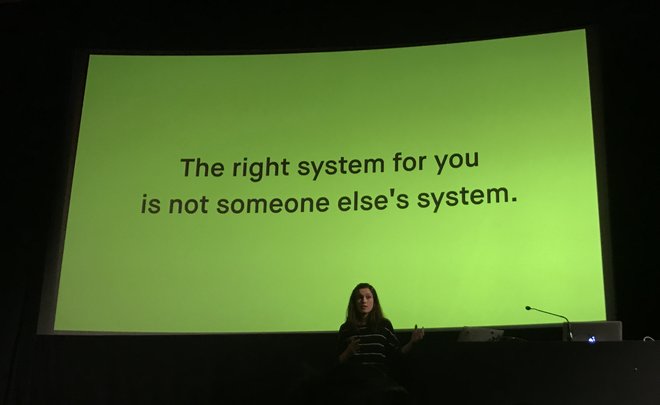

The last talk of the day was by Alla Kholmatova, who has spent years researching design systems and how companies use them. For her forthcoming book, she interviewed style guide people from various large companies. Her talk was about three aspects where design system implementations can differ: strictness, modularity and organisation. The first is about how strictly the system is enforced: are there rules that no one can differentiate from and strict processes for new pattern addition? Or is the system quite loose, and do you rely on your people’s familiarity with the design principles and allow for flexible and expertimental use of those? Modularity then: do you stictly separate everything into modules (high investment, but potentially cost saving in the long term) or is it acceptable to produce designs that are quite specific (and potentially easier to build, but harder to scale)? And lastly, organisation: is it centralised or distributed? Is there one team that creates and vets everything (more reliable, but potential bottleneck), or can people across all teams contribute (more autonomy, but potentially dilutes creative direction)? These three aspects provide a great way to think about what kind of design system works for your organisation. With examples from AirBnB to TED, Alla showed that different companies make different choices on these scales, and she recommended us to make our own choices: ’the right design system is probably not someone else’s design system‘, she concluded.

Alla Kholmatova: the right system for you is not someone else’s system

Alla Kholmatova: the right system for you is not someone else’s system

Takeaways

These are some of my takeaways and things I felt recurred across the different talks:

- Moving from a static page comp approach to working on pattern libraries can completely change our way of thinking about making websites. A pattern page as an isolated test case is one of those things.

- Wholes are just as important as parts: it’s great we spend time on isolated components, but the end user experiences however they’ve ended up being used together, it is important not to lose sight of that.

- There are many complex solutions (like static asset APIs, versioning, templating to serve multiple stacks), but your organisation’s problems may not require them. Keep it simple if you can, introduce more complex solutions if your research shows you have to.

- Marketing your pattern library is a thing, especially in bigger organisations. People can also build web products using their own code or Bootstrap. It’s unlikely for others to promote your pattern library, so if you want it to be success you’ll have to put your sales hat on.

- We aren’t the first people to solve these kind of problems: architects (of buildings) have long worked with modules and wrote at length about making them work in wholes.

In his closing remarks, Jeremy asked if he should do another Patterns Day next year. For what it’s worth, I would love to attend another one! There’s lots more to discuss and a year later, more of our shared problems will have likely been solved by people. I would love to hear more about, for instance, how to test for accessibility in a pattern library world.

I’m looking forward to bringing some of the stuff I learned into practice when coming back to work next week!

Comments, likes & shares (1)

Yesterday I spent all day in a cinema full of design system nerds. Why? To attend Patterns Day 3. Eight speakers shared their knowledge: some zoomed out to see the bigger picture, others zoomed in on the nitty-gritty.

It was nice to be at another Patterns Day, after I attended the first and missed the second. Thanks Clearleft and especially Jeremy Keith for putting it together. In this post, I'll share my takeaways from the talks, in four themes: the design system practice, accessibility, the technical nitty-gritty, and communication.

The design system practice

Design system veteran Jina Anne, inventor of design tokens, opened the day with a reflection on over a decade of design systems (“how many times can I design a button in my career?”) and a look at the future. She proposed we find a balance between standardisation and what she called “intelligent personalisation”.

On the other hand, we aren't really done yet. There are so many complex UX patterns that can be solved more elegantly, as Vitaly Friedman showed. His hobbies include browsing postal office, governmental and e-commerce websites. He looks at the UIs they invent (so that we don't have to). Vitaly showed us more breadcrumbs than was necessary, including some that, interestingly, have feature-parity with meganavs.

Yolijn van der Kolk, product manager (and my colleague) at NL Design System, presented a unique way of approaching the design system practice: the “relay model”. It assigns four statuses to components and guidelines, which change over time on their road to standardisation. It allows innovation and collaboration from teams with wildly different needs in wildly different organisations. The statuses go from sharing a need (“Help Wanted”), to materialising it with a common architecture and guidelines (“Community”), to proposing it for real-life feedback (“Candidate”), to ultimately standardising an uncontroversial and well-tested version of it (”Hall of Fame”).

The technical nitty gritty

Two talks focused on design problems that can be solved with clever technical solutions: theming (through design tokens) and typography (through modular scales with modern CSS).

Débora Ornellas, who worked at Lego (haven't we all used the analogy?), shared a number of great recommendations around using design tokens: to use readily available open source products instead of inventing your own, publish tokens as packages and version them and avoid migration fatigue by reducing breaking changes.

Richard Rutter of Clearleft introduced us to typographic scales, which, he explained, are like musical scales. I liked how, after he talked about jazz for a bit, the venue played jazz in the break after his talk. He showed that contrast (eg in size) between elements is essential for good typography: it helps readers understand information hierarchy. How much depends on various factors, like screen size, but to avoid having to maintain many different scales, he proposed a typographic scale that avoids breakpoints, by using modern CSS features like

clamp()(or a CSS locks based alternative if you don't want to risk failing WCAG 1.4.4). I suggest checking out Utopia to see both strategies in action.Accessibility, magic and the design system

The power of design systems is that they can make it easier to repeat good things, such as well-engineered components. And they can repeat accessibility, but there is a lot of nuance, because that won't work magically.

Geri Reid (seriously, more conference organisers should invite Geri!) warned us about the notion that a design system will “fix” the accessibility of whichever system consumes it. Sounds like magic, and too good to be true? Yup, because what will inevitably happen, Geri explained, is that teams start using the “accessible” components to make inaccessible things. Yup, I have definitely seen this over and over.

To mitigate this risk of “wrong usage”, she explained, we need design systems to not just deliver components, but set standards and do education, too. At which point the design system can actually help build more accessible sites. For instance, if components contain ARIA, it's essential that the consumers of those components know how to configure that ARIA. In other words, design systems need very good documentation. Which brings me to the last theme: common understanding and why it matters.

Mitigating misunderstandings with better communication

The theme that stood out to me on the day: design system teams commonly have to deal with misunderstandings. Good communication is important. What a cliché, you might say, that's like anyone in any job. Yes, but it's specifically true for our field: design systems force collaboration between such a broad range of people. That includes similar-discipline-collaboration, like between designer and developer. Débora explained what can happen if they don't work together closely, or if breaking changes aren't communicated timely.

But it's also about wider collaboration: a design system team also needs to make sense to other departments, that have specific requirements and norms. Including those that don't really grasp all the technical details of front-end componentisation, like marketing or (non-web) brand teams, or the people who can help sponsor or promote the project. Samantha Fanning from UCL focused on this in her talk on “design system buy-in”, which she had a lot of useful tips about. She recommended to involve other departments early to do “co-design” rather than presenting (and surprising) them with a finished product. She also shared how it helped her to add design system work as extra scope onto existing projects, rather than setting up a design system specific project.

In her talk, Mary Goldservant of the Financial Times, also touched on the importance of communication. She shared how they got feedback from stakeholders and manage expectations, while working on a large update to Origami, the Financial Times' brilliantly named design system, that includes lots of changes, like multi-brand and multi-platform support.

Wrapping up

It was nice to hang out with so many like-minded folks and learn from them. A lot of the challenges, tools and ideas resonated. Once again, I've realised our problems aren't unique and many of us are in similar struggles, just in slightly different ways.