In what was a truly inspiring afternoon at the client last week, we watched the English film I, Daniel Blake. It is about a carpenter of nearly the pension age, who applies for income support following a heart attack.

The client is a semi-government organisation that builds software for citizens to manage income support applications online. When I first watched I, Daniel Blake when it came out in November last year, I was moved, but also inspired. This film was about the very thing we were working on, and there was so much to be learned from it.

The plot of the film, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2016, is fairly simple (spoilers ahead). Mr Blake wants to apply for income support, as his doctor has told him he should not work. For some reason, his application gets denied. A mountain of bureaucracy follows soon after. The staff tell him he could appeal, but as an appeal could take months, they recommend him to apply for job seekers’ allowance instead. He does so, but is then asked to prepare a CV and apply for jobs, which he ends up getting offered but cannot take because of the aforementioned doctor’s advice. Mr Blake patiently jumps through all the hoops the system forces upon him, until the point he does not want to take it anymore.

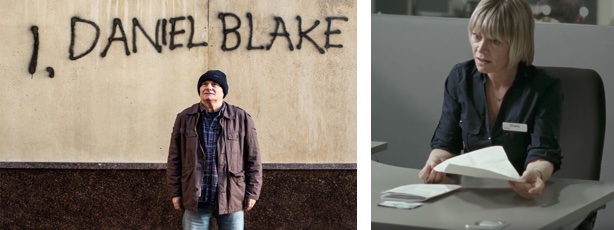

Stills from the film

Stills from the film

People as numbers

In the film, Mr. Blake often tells staff he engages with about his heart condition. He’s the example of a perfectly reasonable person. Yet he finds they ignore what he says, and are only willing to look at what the system says about him (which is: ‘application denied’).

The film shows a bureaucratic system that regards people as applicants, service users or ‘clients’: like numbers. I don’t think that is inherently good or bad. All software that deals with people represents them as fields in a database. I guess this aids efficiency: if all people are in a database, it is easier to make estimates, identify people and their details, et cetera. This only turns into a problem when people are also reduced to numbers. If the number are the only thing the system is interested in.

What happens to Daniel Blake is an example of the latter. Was he treated humanly, a heart attack and a doctor’s recommendation would be plenty of indication for the system to just give him the income support he applied for. Now that he is treated only as a number, the system forces him to jump through hoops needlessly.

Human judgment

Services that used to be mostly physical are transforming to their mostly digital equivalents. Although I am just a front-end developer, I am often involved in teams that realise such transformations. Most of my work revolves around trying to make interfaces easier to use and being inclusive to all who need to use them. I, Daniel Blake was a good reminder that those ambitions can still leave people frustrated.

However user-friendly we try to make our interfaces, a digital service is not going to help everybody. Sometimes the best interface is an actual human being that helps people. Machine judgment is great and efficient, but the system needs human judgment. Equipped with appropriate authorisations, humans trump digital services: the very person sending Mr. Blake to a cv workshop could have just authorised his income support (and gotten on with the next applicant – now that’s efficiency). To help him skip the hoop-jumping.

It was fantastic to get the chance to watch this film with colleagues, and I can’t recommend it enough to peers who work on digital services (government or otherwise). I’ve heard some say it is overly dramatic. It may be, but I found it realistic and close to reality, too. Looking forward to hearing what others think about it!

Comments, likes & shares

No webmentions about this post yet! (Or I've broken my implementation)